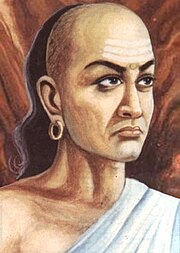

The king Chandragupta Maurya.

♔Chandragupta Maurya

| Chandragupta Maurya | |

|---|---|

Chandragupta Maurya and Jain sage Acharya Bhadrabahu depicted in a medieval stone carving from Shravanabelagola, Karnataka[1]

| |

| 1st Mauryan Emperor | |

| Reign | c. 321 – c. 297 BCE[2][3] |

| Coronation | c. 321 BCE |

| Predecessor | Dhana Nanda |

| Successor | Bindusara (son) |

| Born | c. 345 BCE Pipphalivana near Pataliputraand Ramagrama or Devdaha, close to Magadha (modern-dayNepal and Patna, Bihar) |

| Died | 287 BCE(aged 58) Shravanabelagola, Karnataka (Jain legend)[4] |

| Spouse | Durdhara |

| Issue | Bindusara |

| Mother | Mura [5][6] |

| Religion | Jainism[7] |

| Maurya Empire (322–180 BCE) | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Chandragupta Maurya (reign: c.321–c. 297 BCE) was the founder of the Maurya Empire in ancient India. He was born in a humble family, orphaned and abandoned, raised as a son by another pastoral family, was picked up, taught and counselled by Chanakya, the author of the Arthashastra. Chandragupta thereafter built one of the largest empires ever on the Indian subcontinent. According to Jain sources, he then renounced it all, and became a monk in the Jain tradition. Chandragupta is claimed, by the historic Jain texts, to have followed Jainism in his life, by first renouncing all his wealth and power, going away with Jaina monks into the Deccan region (now Karnataka), and ultimately performing Sallekhana – the Jain religious ritual of peacefully welcoming death by fasting. His grandson was emperor Ashoka, famous for his historic pillars and for his role in helping spread Buddhism outside of ancient India. Chandragupta's life and accomplishments are described in ancient Hindu, Buddhist and Greek texts, but they vary significantly in details from the Jaina accounts. Megasthenesserved as a Greek ambassador in his court for four years. In Greek and Latin accounts, Chandragupta is known as Sandrokottos

Chandragupta Maurya was a pivotal figure in the history of India. Prior to his consolidation of power, Alexander the Great had invaded the northwest Indian subcontinent, then abandoned further campaigning in 324 BCE, leaving a legacy of Indian subcontinental regions ruled by Indo-Greek and local rulers. The region was divided into Mahajanapadas, while the Nanda Empire dominated the Indo-Gangetic Plain.Chandragupta, with the counsel of his Chief Minister Chanakya (the Brahmin also known as Kautilya), created a new empire, applied the principles of statecraft, built a large army and continued expanding the boundaries of his empire.

After unifying much of India, Chandragupta and Chanakya passed a series of major economic and political reforms. He established a strong central administration from Pataliputra (now Patna), patterned after Chanakya's text on governance and politics, the Arthashastra. Chandragupta's India was characterised by an efficient and highly organised structure. The empire built infrastructure such as irrigation, temples, mines and roads, leading to a strong economy. With internal and external trade thriving and agriculture flourishing, the empire built a large and trained permanent army to help expand and protect its boundaries. Chandragupta's reign, as well the dynasty that followed him, was an era when many religions thrived in India, with Buddhism, Jainism and Ajivika gaining prominence along with the Brahmanism traditions. A memorial to Chandragupta Maurya exists on the Chandragiri hill, along with a 7th-century hagiographic inscription, on one of the two hills in Shravanabelagola, Karnakata.

◈Early life

Chandragupta's ancestry, birth year and family as well as early life are unclear. This contrasts with abundant historical records, both in Indian and classical European sources, that describe his reign and empire. The Greek and Latin literature phonetically transcribes Chandragupta, referring to him with the names "Sandrokottos" or "Androcottus".

- The Greek sources are the oldest recorded versions available, and mention his rise in 322/321 BCE after Alexander the Great ended his campaign in 325 BCE. These sources state Chandragupta to be of non-princely and non-warrior ancestry, to be of a humble commoner birth.

- The Buddhist sources, written centuries later, claim that both Chandragupta and his grandson, the great patron of Buddhism called Ashoka, were of noble lineage. Some texts link him to the same family of Sakyas from which the Buddha came, adding that his epithet Moriya (Sanskrit: Maurya, Mayura) comes from Mora, which in Pali means peacock. Most Buddhist texts state that Chandragupta was a Kshatriya, the Hindu warrior class in Magadha and a student of Chanakya. The Buddhist texts are inconsistent, with some including legends about a city named "Moriya-nagara" where all buildings were made of bricks colored like the peacock's resplendent neck.

- The Jain sources, also written centuries later, claim Chandragupta to be the son of a village chief, a village known for raising peacocks.

♔Building the Empire

According to the Buddhist text Mahavamsa tika, Chandragupta and his guru Chanakya began recruiting an army after he completed his studies at Taxila (now in Pakistan).[44] This was a period of wars, given that Alexander the Great had invaded the northwest subcontinent from Caucasus Indicus (also called Paropamisadae in ancient texts, now called the Hindu Kush mountain range). Alexander and the Greeks abandoned further campaigns of expansion in 325 BCE, and began a retreat to Babylon, leaving a legacy of Indian subcontinent regions ruled by new Greek governors and local rulers. A supply of warriors was already in place, and the future emperor and his teacher chose to build alliances with local rulers and a small mercenary army of their own. Chanakya also identified talent for future administration. By 323 BCE, within two years of Alexander's retreat, this newly formed group had defeated some of the Greek-ruled cities in the northwest subcontinent. Each victory led to an expanded army and territory. Chanakya provided the strategy, Chandragupta the execution, and together they began expanding eastward towards Magadha (Gangetic plains).

⬗Eastward expansion and the end of Nanda empire

Historically reliable details of Chandragupta's campaign into Pataliputra are unavailable; the legends written centuries later are inconsistent. According to Buddhist texts such as Milindapanha, which state Chandragupta descended from Sakyas (the family of the Buddha), Magadha was ruled by the evil Nanda dynasty, which Chandragupta, with Chanakya's counsel, easily conquered to restore dhamma. In contrast, Hindu and Jain records suggest that campaign was bitterly fought, because the Nanda dynasty had a well trained, powerful army. Chandragupta and Chanakya built alliances and a formidable army of their own first.

The Mudrarakshasa of Vishakhadatta as well as the Jain work Parishishtaparvan, for example, state that Chandragupta allied with a Himalayan king called Parvatka. It is noted in the Chandraguptakatha that Chandragupta and Chanakya were initially rebuffed by the Nanda forces. Regardless, in the ensuing war, Chandragupta faced off against Bhadrasala, the commander of Dhana Nanda's armies.

In the fictional work of doubtful historicity Mudrarakshasa, Chandragupta was said to have first acquired Punjab, and then combined forces with a local king named Parvatka under the advice of Chanakya, and advanced upon the Nanda Empire. Chandragupta laid siege to Kusumapura (or Pataliputra, now Patna), the capital of Magadha, with the help of mercenaries from areas already conquered and by deploying guerrilla warfare methods. P. K. Bhattacharyya states that the empire was built by a gradual conquest of provinces after the initial consolidation of Magadha.

| Territorial evolution of the Mauryan Empire | |

Conquest of Seleucid northwest regions

After Alexander's death in 323 BCE, Chandragupta and his Brahmin counsellor and chief minister Chanakya began their empire building in the north-western Indian subcontinent (modern-day Pakistan). Alexander had left satrapies (described as "prefects" in classical Western sources) in place in 324 BCE. Chandragupta's mercenaries may have assassinated two of his governors, Nicanor and Philip. The satrapies he fought probably included Eudemus, who left the territory in 317 BCE; and Peithon, governing cities near the Indus River until he too left for Babylon in 316 BCE. The Roman historian Justin, about 500 years later, described how "wild lions and elephants" instinctively revered him, and how he conquered the north-west:

Chandragupta Maurya applied the statecraft and economic policies described in Chanakya's Arthashastra. There are varying accounts in the historic, legendary and hagiographic literature of various Indian religions about Chandragupta, but these claims, state Allchin and Erdosy, are suspect. They add that the evidence is, however, not limited to texts, but include those discovered at archeological sites, epigraphy in the centuries that followed and the numismatic data, and "one cannot but be struck by the many close correspondences between the (Hindu) Arthashastra and the two other major sources the (Buddhist) Asokan inscriptions and (Greek) Megasthenes text".

The Maurya rule was a structured administration, where Chandragupta had a council of ministers (amatya), the empire was organized into territories (janapada), centers of regional power were protected with forts (durga), state operations funded with treasury (kosa).

Infrastructure projects

Ancient epigraphical evidence suggests that Chandragupta Maurya, under counsel from Chanakya, started and completed many irrigation reservoirs and networks across the Indian subcontinent in order to ensure food supplies for civilian population and the army, a practice continued by his dynastic successors. Regional prosperity in agriculture was one of the required duties of his state officials. Rudradaman inscriptions found in Gujarat mention that it repaired and enlarged, 400 years later, the irrigation infrastructure built by Chandragupta and enhanced by Asoka.

Chandragupta's state also started mines, centers to produce goods, and networks for trading these goods. His rule developed land routes for goods transportation within the Indian subcontinent, disfavoring water transport. Chandragupta expanded "roads suitable for carts", preferring these over those narrow tracts that allowed only pack animals.

Chandragupta and his counsel Chanakya seeded weapon manufacturing centers, and kept it a monopoly of the state. However, the state encouraged competing private parties to operate mines and supply these centers. They considered economic prosperity as essential to the pursuit of dharma (morality), adopting a policy of avoiding war with diplomacy, yet continuously preparing the army for war to defend its interests, and other ideas in the Arthashastra.

Arts and architecture

The evidence of arts and architecture during Chandragupta's time is limited, predominantly texts such as those by Megasthenes and Kautilya's Arthashastra. The edict inscriptions and carvings on monumental pillars are attributed to his grandson Ashoka. The texts imply cities, public works and prosperous architecture, but the historicity of these is in question.

Archeological discoveries in the modern age, such as Didarganj Yakshi discovered in 1917 buried beneath the banks of the River Ganges suggest exceptional artisanal accomplishment.It has been dated to the 3rd century BCE by many scholars,but later dates such as 2nd century BCE or the Kushan era (1st-4th century CE) have also been proposed. The competing theories are that the arts linked to Chandragupta Maurya's dynasty was learnt from the Greeks and West Asia in the years Alexander the Great waged war, while the other credits more ancient indigenous Indian tradition.

Succession

After Chandragupta's renunciation, his son Bindusara succeeded as the Maurya Emperor. He maintained friendly relations with Greek governors in Asia and Egypt. Bindusara's son Ashoka became one of the most influential rulers in India's history due to his extension of the Empire to the entire Indian subcontinent as well as his role in the worldwide propagation of Buddhism.

Death

According to Jain accounts written more than 1,200 years later, such as those in Brihakathā kośa (931 CE) of Harishena, Bhadrabāhu charita (1450 CE) of Ratnanandi, Munivaṃsa bhyudaya (1680 CE) and Rajavali kathe, Chandragupta renounced his throne and followed Jain teacher Bhadrabahu to south India. He is said to have lived as an ascetic at Shravanabelagola for several years before fasting to death, as per the Jain practice of sallekhana.

Along with texts, several Jain monumental inscriptions dating from the 7th-15th century refer to Bhadrabahu and Chandragupta in conjunction. While this evidence is very late and anachronistic, there is no evidence to disprove that Chandragupta converted to Jainism in his later life. Mookerji, in his book, quotes Vincent Smith and concludes that conversion to Jain monk provides adequate explanation to Chandragupta's abdication and sudden exit at a relatively young age and at the height of his power. The hill on which Chandragupta is stated in Jain tradition to have performed asceticism is now known as Chandragiri hill, and there is a temple named Chandragupta basadi there.

The Hindu texts acknowledge the close relationship between the Jain community in Pataliputra and the royal court, and that the champion of Brahmanism Chanakya himself employed Jains as his emissaries. This also indirectly confirms the possible influence of Jain thought on Chandragupta.

According to Kaushik Roy, Chandragupta renounced his wealth and power, crowned his son as his successor about 298 BCE, and died about 297 BCE.

thanks for reading....

thanks for reading....

Comments

Post a Comment