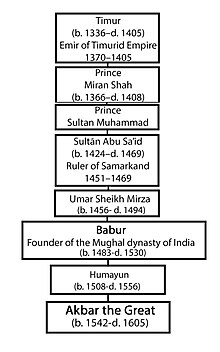

The powerful king of Mughal Empire

Akbar

| Jalal-ud-din Muhammad Akbar جلال الدین محمد اکبر | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Badshah of Mughal Empire Akbar the Great | |||||

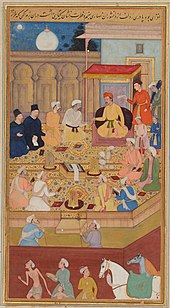

Akbar practising falconry

| |||||

| 3rd Mughal emperor | |||||

| Reign | 11 February 1556 – 27 October 1605[1][2] | ||||

| Coronation | 14 February 1556 | ||||

| Predecessor | Humayun | ||||

| Successor | Jahangir | ||||

| Regent | Bairam Khan (1556–1560) | ||||

| Born | Jalal-ud-din Muhammad 15 October 1542[a] Umerkot, Rajputana (present-day Sindh, Pakistan) | ||||

| Died | 27 October 1605 (aged 63) Fatehpur Sikri, Agra, Mughal Empire (present-day Uttar Pradesh, India) | ||||

| Burial | November 1605 | ||||

| Consort | Ruqaiya Sultan Begum | ||||

| Wives | Salima Sultan Begum Mariam-uz-Zamani Qasima Banu Begum Bibi Daulat Shad Bhakkari Begum Gauhar-un-Nissa Begum | ||||

| Issue | Hassan Mirza Hussain Mirza Jahangir Khanum Sultan Begum Murad Mirza Daniyal Mirza Shakr-un-Nissa Begum Aram Banu Begum Shams-un-Nissa Begum Mahi Begum | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | House of Timur | ||||

| Father | Humayun | ||||

| Mother | Hamida Banu Begum | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam, Din-e-Illahi | ||||

Abu'l-Fath Jalal-ud-din Muhammad Akbar ابو الفتح جلال الدين محمد اكبر (15 October 1542– 27 October 1605), popularly known as Akbar I also as Akbar the Great (Akbar-i-azam اکبر اعظم), was the third Mughal emperor, who reigned from 1556 to 1605. Akbar succeeded his father, Humayun, under a regent, Bairam Khan, who helped the young emperor expand and consolidate Mughal domains in India. A strong personality and a successful general, Akbar gradually enlarged the Mughal Empire to include nearly all of the Indian Subcontinent north of the Godavari river. His power and influence, however, extended over the entire country because of Mughal military, political, cultural, and economic dominance. To unify the vast Mughal state, Akbar established a centralised system of administration throughout his empire and adopted a policy of conciliating conquered rulers through marriage and diplomacy. To preserve peace and order in a religiously and culturally diverse empire, he adopted policies that won him the support of his non-Muslim subjects. Eschewing tribal bonds and Islamic state identity, Akbar strove to unite far-flung lands of his realm through loyalty, expressed through an Indo-Persian culture, to himself as an emperor who had near-divine status.

Mughal India developed a strong and stable economy, leading to commercial expansion and greater patronage of culture. Akbar himself was a patron of art and culture. He was fond of literature, and created a library of over 24,000 volumes written in Sanskrit, Urdu, Persian, Greek, Latin, Arabic and Kashmiri, staffed by many scholars, translators, artists, calligraphers, scribes, bookbinders and readers.

Early years

Defeated in battles at Chausa and Kannauj in 1539 to 1540 by the forces of Sher Shah Suri, Mughal emperor Humayun fled westward to Sindh. There he met and married the then 14-year-old Hamida Banu Begum, daughter of Shaikh Ali Akbar Jami, a teacher of Humayun's younger brother Hindal Mirza. Jalal ud-din Muhammad Akbar was born the next year on 15 October 1542 (the fourth day of Rajab, 949 AH) at the Rajput Fortress of Umerkot in Sindh (in modern-day Pakistan), where his parents had been given refuge by the local Hindu ruler Rana Prasad.

During the extended period of Humayun's exile, Akbar was brought up in Kabul by the extended family of his paternal uncles, Kamran Mirza and Askari Mirza, and his aunts, in particular Kamran Mirza's wife. He spent his youth learning to hunt, run, and fight, making him a daring, powerful and brave warrior, but he never learned to read or write. This, however, did not hinder his search for knowledge as it is said always when he retired in the evening he would have someone read. On 20 November 1551, Humayun's youngest brother, Hindal Mirza, died fighting in a battle against Kamran Mirza's forces. Upon hearing the news of his brother's death, Humayun was overwhelmed with grief.

Out of affection for the memory of his brother, Humayun betrothed Hindal's nine-year-old daughter, Ruqaiya Sultan Begum, to his son Akbar. Their betrothal took place in Kabul, shortly after Akbar's first appointment as a viceroy in the province of Ghazni. Humayun conferred on the imperial couple all the wealth, army, and adherents of Hindal and Ghazni. One of Hindal's jagir was given to his nephew, Akbar, who was appointed as its viceroy and was also given the command of his uncle's army. Akbar's marriage with Ruqaiya was solemnized in Jalandhar, Punjab, when both of them were 14-years-old. She was his first wife and chief consort.

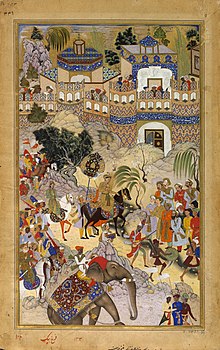

Military campaigns

Military innovations

Akbar was accorded the epithet "the Great" because of his many accomplishments, including his record of unbeaten military campaigns that consolidated Mughal rule in the Indian subcontinent. The basis of this military prowess and authority was Akbar's skilful structural and organisational calibration of the Mughal army. The Mansabdari system in particular has been acclaimed for its role in upholding Mughal power in the time of Akbar. The system persisted with few changes down to the end of the Mughal Empire, but was progressively weakened under his successors.

Organisational reforms were accompanied by innovations in cannons, fortifications, and the use of elephants. Akbar also took an interest in matchlocks and effectively employed them during various conflicts. He sought the help of Ottomans, and also increasingly of Europeans, especially Portuguese and Italians, in procuring firearms and artillery. Mughal firearms in the time of Akbar came to be far superior to anything that could be deployed by regional rulers, tributaries, or by zamindars. Such was the impact of these weapons that Akbar's Vizier, Abul Fazl, once declared that "with the exception of Turkey, there is perhaps no country in which its guns has more means of securing the Government than [India]."

Military organisation

Akbar organised his army as well as the nobility by means of a system called the mansabdari. Under this system, each officer in the army was assigned a rank (a mansabdar), and assigned a number of cavalry that he had to supply to the imperial army. The mansabdars were divided into 33 classes. The top three commanding ranks, ranging from 7000 to 10000 troops, were normally reserved for princes. Other ranks between 10 and 5000 were assigned to other members of the nobility. The empire's permanent standing army was quite small and the imperial forces mostly consisted of contingents maintained by the mansabdars. Persons were normally appointed to a low mansab and then promoted, based on their merit as well as the favour of the emperor.

Capital

Akbar was a follower of Salim Chishti, a holy man who lived in the region of Sikri near Agra. Believing the area to be a lucky one for himself, he had a mosque constructed there for the use of the priest. Subsequently, he celebrated the victories over Chittor and Ranthambore by laying the foundation of a new walled capital, 23 miles (37 km) west of Agra in 1569, which was named Fatehpur ("town of victory") after the conquest of Gujarat in 1573 and subsequently came to be known as Fatehpur Sikri in order to distinguish it from other similarly named towns. Palaces for each of Akbar's senior queens, a huge artificial lake, and sumptuous water-filled courtyards were built there. However, the city was soon abandoned and the capital was moved to Lahore in 1585. The reason may have been that the water supply in Fatehpur Sikri was insufficient or of poor quality.

Din-i-Ilahi

Akbar was deeply interested in religious and philosophical matters. An orthodox Muslim at the outset, he later came to be influenced by Sufi mysticism that was being preached in the country at that time, and moved away from orthodoxy, appointing to his court several talented people with liberal ideas, including Abul Fazl, Faizi and Birbal. In 1575, he built a hall called the Ibadat Khana ("House of Worship") at Fatehpur Sikri, to which he invited theologians, mystics and selected courtiers renowned for their intellectual achievements and discussed matters of spirituality with them. These discussions, initially restricted to Muslims, were acrimonious and resulted in the participants shouting at and abusing each other. Upset by this, Akbar opened the Ibadat Khana to people of all religions as well as atheists, resulting in the scope of the discussions broadening and extending even into areas such as the validity of the Quran and the nature of God.

Akbar's effort to evolve a meeting point among the representatives of various religions was not very successful, as each of them attempted to assert the superiority of their respective religions by denouncing other religions. Meanwhile, the debates at the Ibadat Khana grew more acrimonious and, contrary to their purpose of leading to a better understanding among religions, instead led to greater bitterness among them, resulting in the discontinuance of the debates by Akbar in 1582. However, his interaction with various religious theologians had convinced him that despite their differences, all religions had several good practices, which he sought to combine into a new religious movement known as Din-i-Ilahi.

It has been argued that the theory of Din-i-Ilahi being a new religion was a misconception that arose because of erroneous translations of Abul Fazl's work by later British historians.

Relation with Hindus

Akbar decreed that Hindus who had been forced to convert to Islam could reconvert to Hinduism without facing the death penalty. In his days of tolerance he was so well liked by Hindus that there are numerous references to him, and his eulogies are sung in songs and religious hymns as well.

Akbar practised several Hindu customs. He celebrated Diwali, allowed Brahman priests to tie jewelled strings round his wrists by way of blessing, and, following his lead, many of the nobles took to wearing rakhi (protection charms). He renounced beef and forbade the sale of all meats on certain days.

Relation with Jains

Akbar regularly held discussions with Jain scholars and was also greatly impacted by some of their teachings. His first encounter with Jain rituals was when he saw a procession of a Jain Shravakanamed Champa after a six-month-long fast. Impressed by her power and devotion, he invited her guru, or spiritual teacher, Acharya Hiravijaya Suri to Fatehpur Sikri. Acharya accepted the invitation and began his march towards the Mughal capital from Gujarat.

Akbar was impressed by the scholastic qualities and character of the Acharya. He held several inter-faith dialogues among philosophers of different religions. The arguments of Jains against eating meat persuaded him to become a vegetarian. Akbar also issued many imperial orders that were favourable for Jain interests, such as banning animal slaughter. Jain authors also wrote about their experience at the Mughal court in Sanskrit texts that are still largely unknown to Mughal historians.

Death

On 3 October 1605, Akbar fell ill with an attack of dysentery (possibly from drinking contaminated water from the Ganges river), from which he never recovered. He is believed to have died on or about 27 October 1605, after which his body was buried at a mausoleum in Sikandra, Agra.

Seventy-six years later, in 1681, Akbar's great-grandson, Aurangzeb, pursued oppressive policies and gave orders to demolish Hindu temples. The Jats rose against his policies under the leadership of Raja Ram Jat. They took control of Agra shortly, and ransacked Akbar's tomb. They plundered and looted all the gold, jewels, silver and carpets.

Legacy

Akbar left a rich legacy both for the Mughal Empire as well as the Indian subcontinent in general. He firmly entrenched the authority of the Mughal Empire in India and beyond, after it had been threatened by the Afghans during his father's reign, establishing its military and diplomatic superiority. During his reign, the nature of the state changed to a secular and liberal one, with emphasis on cultural integration. He also introduced several far-sighted social reforms, including prohibiting sati, legalising widow remarriage and raising the age of marriage. Folk tales revolving around him and Birbal, one of his navratnas, are popular in India.

Citing Akbar's melding of the disparate 'fiefdoms' of India into the Mughal Empire as well as the lasting legacy of "pluralism and tolerance" that "underlies the values of the modern republic of India", Time magazine included his name in its list of top 25 world leaders.

thanks for reading ....

thanks for reading ....

Comments

Post a Comment